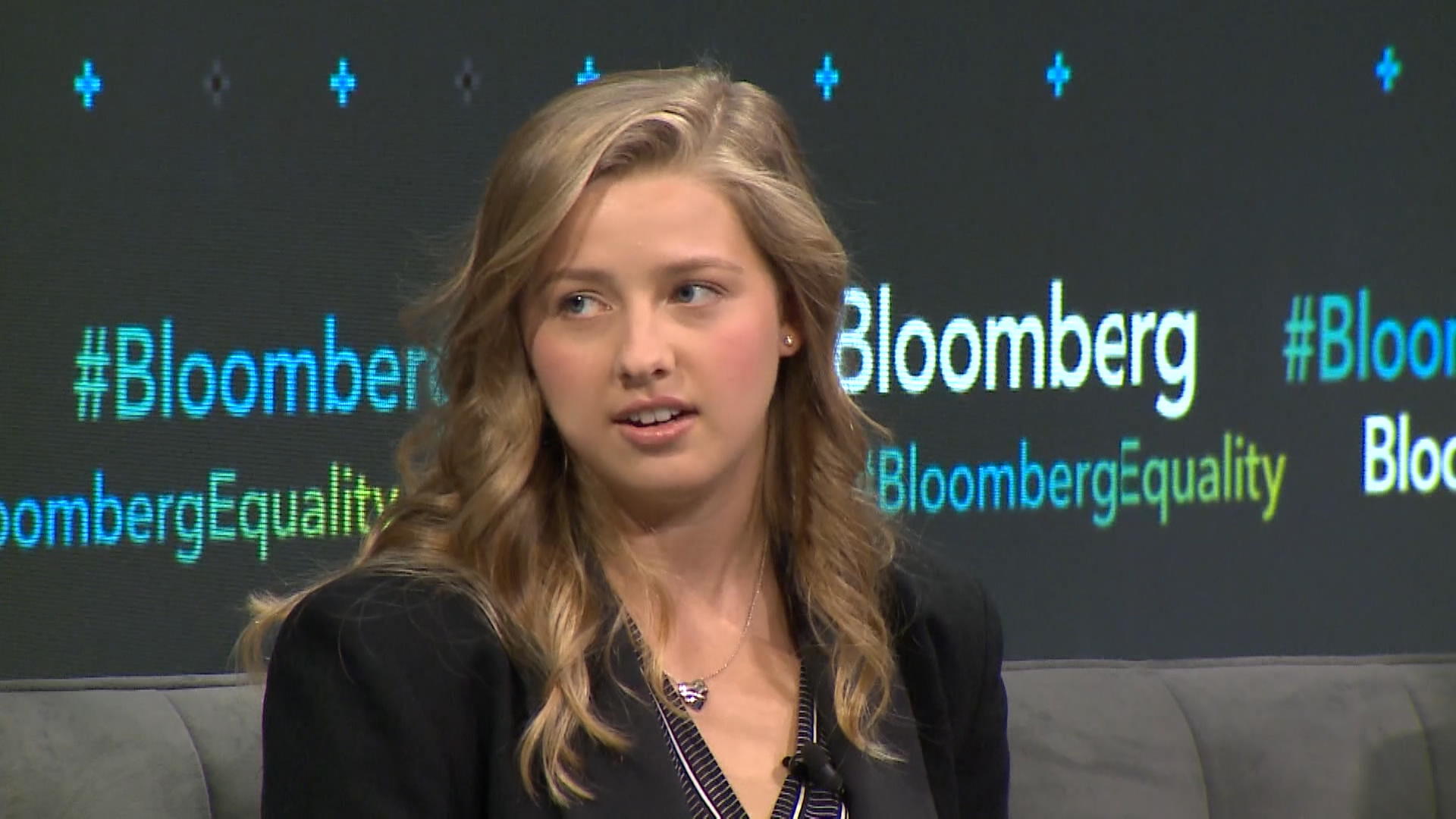

Many are quoted from directly in the book, including denigrating messages between Labrie and other male students.Īs much as possible, they verified Prout's memories of conversations with those she had them with. Abelson - who took a three-month leave of absence from her job to move to Florida to write the book with Prout - said they relied on Prout's journal, text messages, Facebook messages, emails, legal documents and even college application essays as source documents. Writing the book was a journalistic investigation in and of itself, the co-authors said. "School leaders turned a blind eye fellow students shamed those who spoke out against this culture and administrators, trustees, and alumni tried to silence victims. Earlier this year, the school settled a civil lawsuit filed by Prout's parents.)Ībelson reported on similar institutionalized behavior during an investigation into sexual misconduct in private schools that uncovered "pervasive sexism and entitlement that enabled male teachers and students to prey upon girls," she writes in an afterword in the book. Paul's said Prout "misrepresents" the school's culture. (In a statement after the book's release, St. "I struggled to make sense of it all at the time, because the behavior was so normalized, woven into the fabric of St. "I would quickly learn that boys at this school felt entitled to stake a claim to things that were not their own, including girls' bodies," she writes. Paul's darker side: intense social hierarchies with deep roots in the school's history as an all-male institution. Admission there was her dream, especially after Prout's family was uprooted from their home in Japan following a serious earthquake. Paul's was so devastating for Prout, whose older sister and father attended the prestigious boarding school. The book explains why what happened at St. dress the way I want to say 'no,' and be listened to." It was inspired by Prout's young sister's suggestion that "girls need a bill of rights." Prout's early rights included "I have the right to. The book is named for a social media campaign she launched to help others reclaim their own voices and find empowerment in pain. "Sexual assault is a crime of power and control so it's so important to put the power and control back in the survivors' hands," Prout said. In an interview with the Weekly, Prout and Abelson said the book aims to both hold such institutions accountable and chip away at the stigma associated with sexual violence. It's a powerful narrative of the isolation, shame and self-doubt survivors of sexual violence experience and a defiant challenge to the institutions that failed to protect her and other young women and men from such violence. The book, which she co-authored with Jenn Abelson, an investigative reporter on the Boston Globe's Spotlight Team, documents the painful aftermath of the crime, the backlash she and her family experienced in their legal battle and Prout's path to advocacy. In a new book, "I Have the Right To," Prout continues to reclaim her voice. Publicly, Prout remained an anonymous, faceless victim for months until she decided to reveal her identity - and reclaim her voice - on the Today Show in 2016. Labrie was later convicted of three counts of misdemeanor sexual assault for penetrating a minor and a felony charge of using a computer to lure a minor but not of the more serious felony sexual-assault charges he faced. Labrie had invited her to a "Senior Salute," a tradition in which male seniors competed with one another to have sex with as many younger girls as possible before graduation. Paul's School in New Hampshire who she said had raped her on campus when she was 15 years old. In 2015, Prout took the witness stand to testify against Owen Labrie, a 19-year-old graduate of St. Months before dozens of women accused Harvey Weinstein of sexual misconduct, before a jury found Bill Cosby guilty of sexual assault, before Brock Turner would be sent to jail for sexually assaulting an unconscious woman a Stanford University, a 16-year-old girl was taking on what she saw as institutionalized rape culture at her elite East Coast boarding school. Jenn Abelson, a reporter on the Boston Globe's Spotlight Team and co-author of "I have the Right To: A High School Survivor's Story of Sexual Assault, Justice and Hope." Photo courtesy Simon & Schuster.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)